Advancements in technology and science, especially in AI-powered speech tools, in the last two decades have helped us make strides in assisting those who need it, especially those with mental or physical disabilities. But developing new tech and methodologies compares better to a marathon than a sprint, and progress is not linear, however urgent it feels.

One community acutely experiencing this, especially during the pandemic, was autistic children and their families.

Besides higher morbidity and mortality rates related to COVID-19, lockdowns during the earlier stages of the pandemic had an outsized impact on the psychological development of children with autism. Isolation and the circumstantial uncertainty of the pandemic caused uncertainty and a constant flow of distressing information. Autistic children were often deprived of therapeutic intervention and switched to online education and home training, an inadequate substitute for in-person help.

Studies from the World Journal of Virology showed that the lockdown significantly and adversely affected sensory-motor development, cognitive abilities, sleep, morale, behavior, and social interactions in about 50% of children with special needs. It also interrupted their language development. For non- or minimally-verbal kids, this delay could be profoundly impactful and far-reaching.

For these children, the progress of educational tools that could offset this disadvantage was urgent indeed. As the world adopted digital communication, advancements in home solutions for autistic children and their families sped up too. Since then, we’ve seen encouraging developments in alternative and augmentative communication (AAC) tools, which help people communicate and learn to converse in ways besides talking. Until the last twenty years, most common-use AAC tools employed writings and drawings on flashcards. More recently, iPads and file sharing have made AAC easier.

Some tools have allowed parents to link uploaded images to prerecorded phrases, helping nonverbal people to familiarize and practice using specific, functional definitions. In the past, speech-generating devices (SGDs) have shown potential in helping some autistic individuals with simple communication, such as requesting skills. With premade graphics on a tablet in an SGD called SPEAKall!®, nonverbal autistic participants in a 2019 study learned to combine “I Want” symbols with “Item” buttons to ask for food or toys.

Though they prompted interactions that were relatively simple in nature, the flexibility of technology showed potential for SGDs.

But with recent advancements in artificial intelligence for AAC tools, the marathon has come closer to a sprint. While pandemic-era technology showed some progress in helping children increase spoken words, the flexibility and speed of AI-augmented tools show promise to stimulate fuller conversations – a critical part of a non- or minimally-verbal child’s development, and a new way for them to have mutual, loving exchanges with their parents.

AI allows AAC apps to interpret visual scenes in photographs, or people’s faces, and generate topics or vocabulary based on them in real time. This is a momentous new ability for non-speaking individuals and those helping them; the flexibility to add and store photos and vocabulary symbols dynamically streamlines language learning. Programs like QuickPic, a learning app that uses an LLM to generate relevant vocabulary from images, are easy to download and use.

A 2024 study around the usability and quality of QuickPic (accessible at https://www.mdpi.com/2934580) showed benefits reported by speech-language pathologists, including the expansion of utterance length, targeting specific communication goals, and actually increasing ability to communicate about specific topics or activities.

From flash cards and drawings, to the convenience of an iPad, to automatically generated topics and images from individual image uploads – in just the last five years, we’ve made huge steps in streamlining how caregivers can help nonverbal children learn to communicate! Linking images to words helps kids communicate their needs, and sometimes learn to form sentences.

But communication, ideally, is at least a two-way street – for their uses as learning tools, SPEAKall! and QuickPic do not necessarily stimulate conversation. For parents, conversations with their nonverbal children require more than abstract understanding of vocabulary.

Both during the pandemic and in general, this is a source of angst for many parents of non- or minimally-verbal autistic kids. Every parent wants to talk to their child, to understand and be understood, to the greatest degree possible.

Combined with a robust communication tool, AI can create and provide materials with structure for parents to start two-way conversations with their minimally verbal children that incorporate balance and reciprocity.

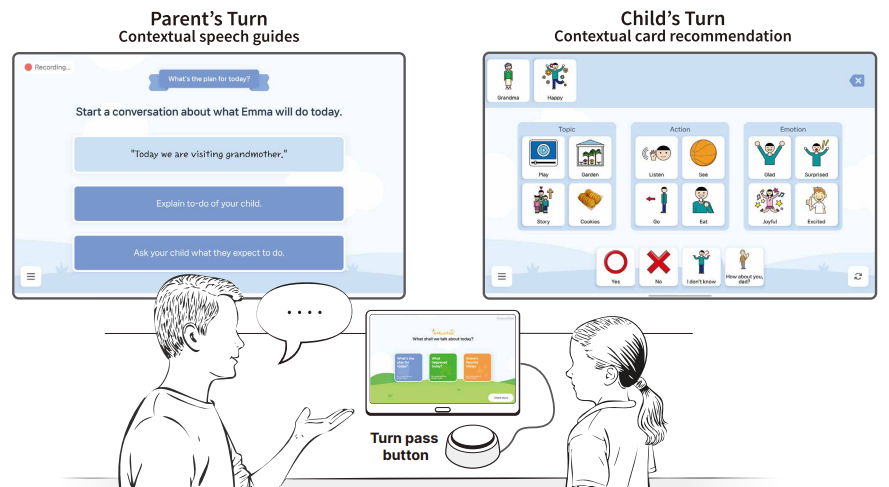

For example, researchers in South Korea have developed a communication mediation system that runs on a tablet, with a physical button sitting between the parent and child. The system, called AACessTalk, helps parents and their kids shape turn-taking conversations, pushing the button to switch speakers. It also listens and provides real-time guides for the parent to engage the child, picking up on subtleties in responses, and generating guide or example messages.

Like the QuickPic tool, AACessTalk links vocabulary to images. After choosing a conversation topic together on the tablet, the parent speaks first and presses the turn-pass button. Immediately the child receives vocabulary cards in Topic, Action, and Emotion categories, based on the selected topic and parent’s prompt. Along with some generic “core” cards like “yes” and “no,” the child selects a series of cards that can form a concept or sentence. Then the child presses the turn-pass button.

The process continues for the length of a conversation, with the tool providing dialogue analysis and feedback for the parent, including flagging potential negative conversational patterns for the parent to avoid. After a few exchanges, the parent or child, if they wish, can select an “end conversation” button. The tool provides encouragement and feedback to the participants afterward.

The AACessTalk tool, and future tools like it, can allow parents to create structured conversations with their minimally verbal children at home, in a safe and predictable setting, and in a way that meets the child where they are in their development. Children who need more guidance can rely more on the Topic, Action, and Emotion cards to answer their parents. Children with more to say can simply use them as inspiration.

And just as the child gets practice forming conversations, a 2025 study of AACessTalk’s functionality showed that parents learned key skills, too. The tool’s built-in guides gave parents ideas to respond in varied ways to their children, even in repetitive situations, breaking the routines that had led to children giving pre-memorized answers to familiar questions.

Parents saw exciting results from taking the tool’s advice. After receiving an AI-generated prompt to try a very simple response during a conversation, one study participant remarked:

“I’d read about praising and empathizing in books, but this was my first time trying it. I thought the conversation would just end if I said something like that. But when I said, ‘Wow, that’s awesome,’ my child’s face lit up, and they got more engaged. So I kept reacting, the conversation kept going, and it felt like we were really talking.”

More than previous AAC tools, this one creates an opportunity for reciprocal conversation and learning – and the study found these opportunities coming to fruition, to the surprise of participating parents.

There are four “core” cards that appear on every screen for the child’s half of the conversation. Alongside the predictable “No,” “Yes,” and “I don’t know,” the tool’s developers added a question option: “How about you, Mom/Dad?” In an introductory session, every parent participant in the study mentioned that their child would not likely use this card, as they had never asked such a question before.

But they did. One parent shared their happy surprise at being asked a question by their child:

“Usually, I’m the one asking all the questions, and it gets pretty lonely. But when [child] used the ‘How about you, Mom?’ card, it was so sweet and touching. It really felt like [child] cared. I got all excited and, for the first time, shared my own story with my child. It felt like we were in conversation ‘together,’ like we were connected.”

Of course – even when it doesn’t feel like that, even when the means of the parent and child don’t allow for this kind of conversation, they are still fundamentally connected. AACessTalk didn’t create the bond between parent and child; with its flexibility, suggestions, and ease of use, it helped them both joyfully find and expand on it.

By providing structure and a wealth of nonverbal cues in real time, AI with AAC tools can redefine conversational boundaries and address the specific needs of both parties, parents and children, to form their own conversations and learnings.

It’s cases like these where AI finds some of its most impactful uses: when integrated into speech tools that have already shown potential results, making them faster and easier to use, subverting their limitations, and providing feedback on optimal use.

In many cases, study participants had richer and fuller conversations with their children than they thought possible. Said one parent,

“Funny how I realized the things I’ve been saying here are just like what I used to tell my child every day before the autism diagnosis. He was just a baby then, but I talked to him so much. But after the diagnosis, I stopped and only gave simple commands, thinking that conversations like this wouldn’t be possible. But when we tried, it turned out we could do it. I was the one who was trapped in this mindset while my child was growing in their own way all along.”

For the first time we’re learning, beyond efficiency, what a profound impact AI with AAC tools can make on families: helping them discover the breadth of connections they could make with each other.